Most firms pride themselves on being meritocracies, yet financial services firms are increasingly struggling to rationalize a pay for performance culture.

While other industries face many of the same challenges, it is particularly acute in financial services as the industry tries to make sense of the connection between culture and crime, how to measure performance, and whether there is a way to incent profitable outcomes without incenting the wrong kind of behavior. One more level of complication in considering this topic, is that across a number of industries, firms may think of themselves as being meritocracies without a formal external point of reference – how do we really know if we are one, anyway?

In this article we will discuss the advantages of being a meritocracy. The obstacles firms face. The various techniques for promoting this culture and the pitfalls firms may face when they don’t.

What Can Happen If You Don’t?

It is simplest to frame the topic in the context of a series of mini case studies – These are all based on real life stories, or composites of such:

FinTech Departure Consider the case of Mary, who had a senior risk management role at a bulge bracket firm. Mary was very good at her job, and had a unique approach to modeling out risk scenarios that had potential utility outside her firm in the competitive market. Mary knew her firm would be slow to explore the possibilities her techniques represented. She also knew that they could not begin to pay her more than a modest increase over her current, effectively capped total compensation.

Mary left and started her own Fin Tech shop, earning more than her former employer could have paid her, and having a large equity stake in her own company. Her prior employer did not have adequate corporate speed to bring her product to market, nor did they have a pay structure that allowed for rewarding someone with Mary’s capabilities. Their pay structure couldn’t hold a performer at Mary’s level. Yet her firm was investing heavily in creating “greenhouses” for innovation. They could rationalize spending tens of millions of dollars on these greenhouses in the hopes of building a fin tech capability, but could not rationalize a pay structure that could retain someone like Mary. This is a theme in firms that do not embrace meritocracy: relative carelessness on aggregate compensation spend, excessive focus on capping individual pay.

M&A Start-Up Consider the case of Bill, an M&A banker at a large multinational bank. Bill was a strong performer, very entrepreneurial – ideal talent for a large investment bank’s needs, post 2008. Bill could see on the horizon a slew of high fee transactions –bringing in as much as 50 million dollars of fees in a year, compared to 10 million from the second highest producing banker at his firm, but the firm would only pay Bill about a million or two more than the number two producer. With that, Bill left to start his own boutique firm, earning more than his former employer could pay him, and having a large equity stake in his own company.

Consulting Performance Subsidy Consider the case of a large consulting firm that tracks billable hours with great precision, and relies on this metric as the ultimate measure of employee performance. High performers at the firm bill out at almost 2X the number of hours as low performers, and they are paid about 15 percent more on total comp. So, in essence, the compensation cost of getting a billable hour from a low performer is huge compared to the cost of getting a billable hour from a high performer. Ultimately, this firm isn’t focusing on aligning performance and reward, and missing an opportunity to both save comp cost on lower performers AND better retain high performers. And the firm has no immediate plans to change this. They are comfortable with the idea that they significantly overpay low and average performers relative to their contribution.

Boutique Brain Drain The ultimate cautionary tale is an investment banking boutique – let’s call it “Good Advice”. At investment banking boutiques – and many other types of firms – it is easy to see who the producers / contributors are. Good Advice had a bad year. Of their 20 bankers, only five produced – the balance executed almost no transactions. The CEO hated the thought of zero bonuses or even relatively small bonuses for the non-producers, so the five producers were paid a fraction of what would be an industry standard for their contribution. Shortly thereafter, two out of the five producers left – they lost confidence that Good Advice could pay them competitively, and now Good Advice has gone into a downward spiral. Missing two of their high producers, the next year the firm performed even worse, so the remaining three high producers had to further subsidize their low performing colleagues – so they left too. Now all the firm has left is a group of non-performers. It isn’t hard to guess how the firm has fared.

So, what is the common theme in these case studies? A firm’s refusal to pay for performance virtually pushed out the very people who could have made the firm stronger.

Obstacles

As we think about building a meritocracy, there are a set of obstacles we hit consistently. All of them can be mitigated – some more easily than others.

Year-Over-Year Approach to Pay

The first obstacle is firms’ tendency to manage compensation on a year-over-year basis, vs. marking to market the actual performance. A startlingly high number of firms think about employees’ pay very carefully at the point of recruitment, and then simply give incremental increases or decreases based on market conditions, firm performance, individual performance, etc. Compensation managed in this fashion will rarely keep pace with volatile contributions, and worse still, doesn’t create a meaningful incentive for staff to outperform.

Performance Management Woes

The second obstacle to consider is that many firms manage and measure performance so poorly that they cannot even entertain highly differentiated pay because they struggle to identify the high performers in a systematic way. This is where firms should hold themselves to higher standards - it isn’t acceptable to simply say “we can’t really tell who performs well or not”. The fundamental underpinning of a meritocracy is the ability to measure performance.

Incenting Unethical Behavior

Another obstacle to building a meritocracy is the notion that you cannot incent someone to perform well without unintentionally incenting unethical behavior. This point of view winds up getting reinforced by regulators in the financial services industry. As you can imagine, if a firm has this point of view as a guiding principle in how they think about reward, then the high performers will quickly self-select out of this organization. Firms can too quickly and simplistically look at unethical conduct and assume that eliminating incentives for high performance would mitigate this conduct. In practice, there is a broad swath of work to be done around culture, controls, risk management and incentives that can effectively prevent unethical conduct. Encouraging mediocre performance within a firm is in fact unethical treatment of the firms’ shareholders – who wants to hold shares in a firm that doesn’t encourage excellence?

Tenure Driven Promotions

A fourth obstacle that is not pay focused is a tendency to provide tenure driven promotions. A strong tool to be used in building a meritocracy is to have faster career progression for high performers. Firms accustomed to promoting based on tenure vs contribution/capability risk losing or disengaging high performers who both want the recognition of a promotion, but also want to have their ideas heard and respected. We in the HR community need to challenge ourselves to say to the business “yes, we can identify performance, we can identify staff that are ready for progressive responsibility, we can promote people based on capability and achievement – we needn’t simply rely on years of service as a proxy for readiness.”

Fear of Transparency

Fear of transparency is a great obstacle to building a meritocracy. If firms hyper reward their best performers and the other employees find out, managers will have to have challenging conversations with their ordinary performers to explain why they are not extraordinary. Firms should embrace these conversations as healthy and necessary to help employees develop or exit the organization, but firms often fear these conversations. The average performers wind up cheated out of the kind of challenging discussions that can propel them forward.

Fixed Pay Focus

As some number of firms have begun to shift more and more compensation into fixed pay, it has become increasingly difficult to really differentiate compensation. When 90% of the pay for a role is in salary, and there is a relatively narrow range for incentives, how can you really differentiate pay? What kind of special reward are you holding out for a special contribution?

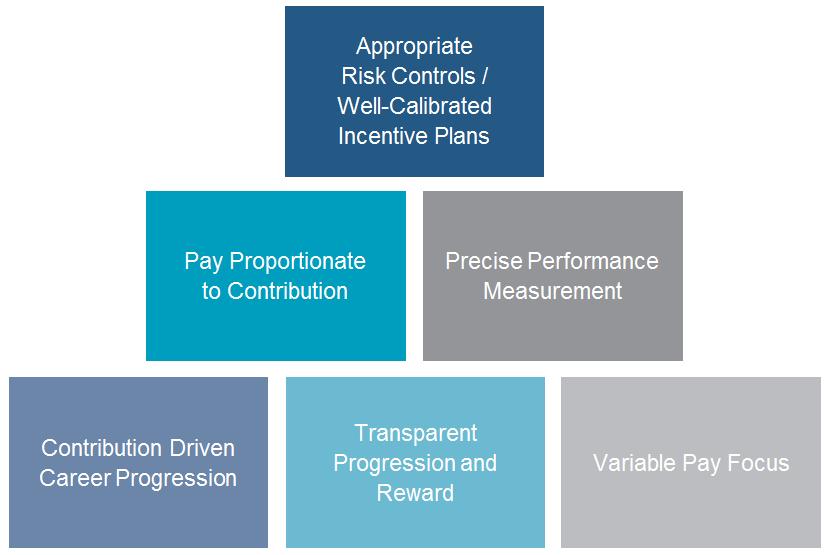

Building Blocks

The very things that feel like obstacles to having a meritocracy can be turned on their heads to be the building blocks for establishing one. None of these things are easy – but all can be achieved with some passion, imagination and perseverance.

Pay Proportionate to Contribution As we look at firms’ pay data, we often measure “differentiation” – what is the difference between what a firm pays a low performer and a high performer, or an average performer and an extraordinary performer. Not surprisingly, there is a strong correlation between differentiation and firm performance. Interestingly, a number of firms will pay a high performer somewhere around 30% more than an average performer. As a cohort, human capital and compensation professionals feel comfortable with a number in this range. But how did we get here? What does this mean? Are there performers who contribute 200% more than their peers? Even in non-revenue producing roles, haven’t we all worked with colleagues whose contribution is easily that of 3 or 4 peers? Do we think a 30% premium is appropriate to recognize this out-performance? Why not 25%? Why not 35%?

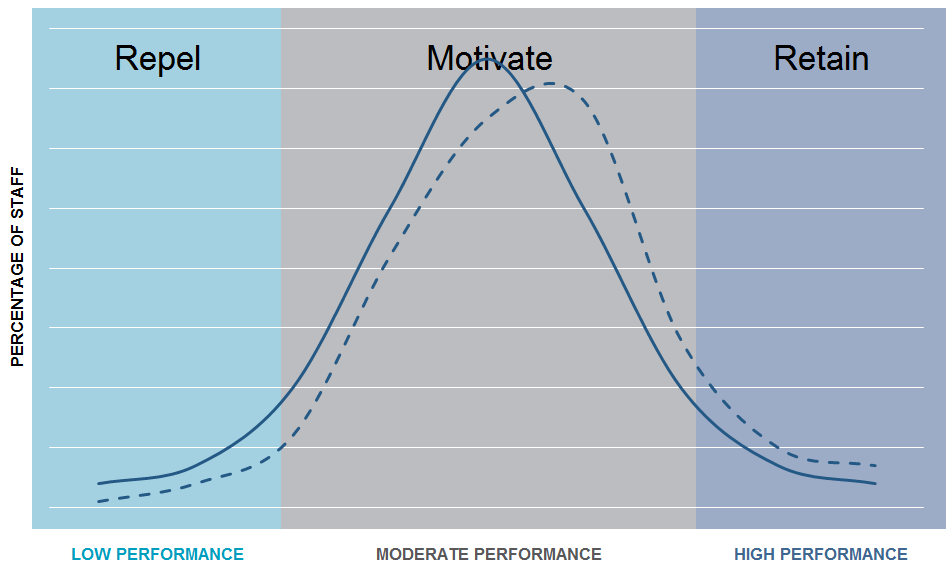

In many ways this begs the question, what is our intention for differentiating pay. Is this premium paid to the high performer even intended to be proportionate to begin with? Or is it simply a nod, to say “keep it up – we know you are worth more”. Experience has shown that high performers don’t need appropriate pay to motivate them – you need appropriate pay to retain them.

Consider the graph below – at the extreme ends of high and low performance, pay usually has little influence on performance. A well-designed pay program should effectively repel low performers, retain high performers, and then motivate the middle of the pack.

Contribution Driven Career Progression Being a meritocracy isn’t just paying high performers more – it is recognizing contribution for what it is, and not confusing it with tenure. Part of what has attracted young talent to tech firms in recent years, beyond perks and brand recognition, has been the perception that you can walk in the door and have impact. As firms get larger, even in the tech space, but certainly at consulting firms and financial services firms, they rely more heavily on tenure as a tool to determine career progression. Why? Because it is easier; does it work well?

A number of our clients have dynamic job evaluation systems that account for varied skills, accountabilities and specialisms which promote mobility and development. These systems are completely de-linked from tenure. Firms embracing this approach see better employee development, greater transparency around what it takes to advance, faster progression for high performers, and mitigation of title inflation. This is an important one. Lower performers stop getting promoted based on tenure, and so compensation dollars are saved. Not overspending on low performance is as integral to a meritocracy as rewarding high performance.

Variable Pay Focus We have seen variable pay consistently shrinking at financial services firm over time, while growing at consulting firms. The reasons at financial services firms are threefold: responding to regulatory environment, feeling the need to compete with tech firms, where the pay was historically more salary focused, and the growing lack of confidence in the ability to really determine who is a high performer – particularly in support area jobs. Consulting firms have been focusing a higher percentage of their compensation on variable pay in an attempt to have greater differentiation.

One of the biggest pitfalls of a high fixed pay focus is the incremental baseline cost, which in a low performing year, makes it virtually impossible to reward the individual high performers. How can one think that increasing fixed costs on an overall basis is a good way to make the financial services industry more stable?

An important maxim of compensation design strategy is that a plan should be judged by how well it attracts the right cultural fit, as well as how well it repels a poor cultural fit. Firms that focus minimal dollars on fixed pay leave lots of money for variable pay. When a candidate interviews he is offered the opportunity to join a meritocracy and make a big bet on his own performance. Candidates who don’t want this risk are bad cultural fits and don’t belong in the firm. Instead of looking at the focus on variable pay as a competitive disadvantage, look at it as a cultural differentiator – a way to fill the firm with hungry, confident performers who are willing to be paid based on their performance.

Precise Performance Measurement A few key themes emerging as arguments / challenges to the anti- performance ratings movement are as follows:

Giving employees more frequent and better feedback does not require eliminating assessment (see “Reimagining Performance Management” by Levi Segal and Seymour Adler)

- Training and selecting managers to be good performance managers is critical to a firm’s success

- Firms need to stop side-stepping the tough conversations and be candid and transparent about what it takes to be a high performer

Beyond this, there is much work to be done. Most performance management focuses on “how well”, but not on “how much”. If we truly want to align reward to contribution, we need to get more skillful at determining measures for non-revenue producers that quantify contribution and impact rather than simply say “the work that was done was done well”.

Appropriate Risk Controls / Well Calibrated Incentive Plans Firms risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater when they look at events like the Wells Fargo crisis and assume that incentive plans in general, are bad. While these areas will have connectivity, we need to be clear on what the accountabilities are for risk management vs. compensation design and design plans that promote performance and discourage unethical behavior. Firms in the Wealth Management space (see “Implications of New FLSA Minimum Salaries and DOL Fiduciary Ruling by Todd Crowley, Paul Wagner, and Peter Keuls) are shifting Wealth Managers’ incentive structures to measure client results vs. internal fees; it doesn’t take great imagination to construct measures that create a win-win objective for firms and their clients. Practices like capping incentives, decreasing percentage payouts for progressive levels of production, moving towards standardized incentive payouts because we are afraid of the behavior they may encourage is tantamount to saying, “we can’t really think about how to create the right measures so we would rather not risk encouraging high production”.

Transparent Progression and Reward Firms have the opportunity to be more candid and open about what they want, and what they offer in exchange. The skills, behaviors and achievements they are seeking, and the kinds of outcomes it will create for employees – whether these outcomes are in the area of career progression or financial reward. The employer / employee relationship is in fact a relationship like many others. The clearer we can be about what we want, the more likely we are to get it. And the clearer we can be about what kinds of rewards are out there, both for high and low performance, the more apt we are to engage and retain the kinds of employees we want.

Conclusion

As firms continue to feel pressure for growth in an environment of increasing competition, the competitive edge can as often be the culture as a new product or market or service. Even large companies’ success is often driven by small numbers of high impact people. The retention and engagement of these people, at all levels of seniority create splashes of excellence that ripple out and slowly touch more and more of an organization. Meritocracies attract these people; promote great quality work, high standards, and a contagion of excellence that inevitably leads to success.

Steering a firm towards being a greater meritocracy is hard work, and doesn’t happen overnight. The first step is to know who you want to be. The second is benchmarking where you are, to see how far you have to go. The rest follows with reinforcing principles and a commitment to the change.